Recently, Michael Kitces published an article titled, “Why Paying Yourself 5% Interest On A 401(k) Loan Is A Bad Investment.” My first thought was, “If it’s a bad idea for a 401(k) loan, it must be even worse for Thrift Savings Plan loans.” After all, the interest on a TSP loan is nowhere near 5%…it’s tied to the G-Fund interest rate. At the time of this writing, that would be 2.25%. In other words, that’s less than than half of the 401(k) loan mentioned in Kitces’ article.

But that’s not why I wrote this article. After all, I didn’t know whether people actually took out TSP loans. As a matter of fact, they do. According to Government Executive, TSP participants took out more in loans in 2015 than in 2014: $4 billion compared to $2.9 billion. In comparison, TSP participants took age-based withdrawals of $2.2 billion and $2.1 billion, respectively. Age-based withdrawals are ones that you can make after 59 ½ without early withdrawal penalty. In other words, TSP participants took out more in loans than they did in withdrawals aligned with the typical retirement strategy.

This discovery led me to these two questions:

- “Why would someone take a TSP loan?”

- Are there any situations in which a TSP loan would make sense?

That’s what this article is about. But first, some TSP loan basics.

Table of Contents

Thrift Savings Plan Loan Basics

In order to understand this, we need to better understand more about TSP loans. Below are some fundamental details.

How much can you borrow? A TSP loan is when you take money from your TSP account for personal use. The loan amount can range from $1,000 to $50,000, but cannot exceed:

- Your contributions & earnings on those contributions

- The greater of $10,000 or 50% of your vested account balance (minus any outstanding loan balance)

- $50,000 minus your highest outstanding loan balance (at any point within the past 12 months)

Types of loans: A general purpose loan requires no documentation. However, you must repay the loan within 5 years. For a residential loan, you must provide supporting documentation. This is to verify that the proceeds will be used for the purchase or construction of a primary residence. In this case, you can amortize the loan over a 15-year period. For either type of loan, payments must start within 60 days of the loan disbursement.

Interest: Interest is calculated as the interest rate of the G-fund at the time the loan is processed. As of August 2017, this was 2.25%. TSP loan payments are not tax deductible. However, the interest paid goes back into your TSP account.

Fees: All loans require a $50 administrative fee. This is taken directly from the loan proceeds. For example, a $10,000 TSP loan will result in net proceeds of $9,950. However, the loan will still be for $10,000.

Loan Eligibility Requirements: The following are requirements for any TSP loan, whether it’s a general purpose loan or residential:

- Must be employed by the Federal Government or a member of the uniformed services.

- Must be in pay status because repayments are set up as payroll deductions.

- Can only have one outstanding general purpose loan and one outstanding residential loan from any one TSP account at a time.

- Must have at least $1,000 of your own contributions and earnings in your TSP account (agency contributions and earnings cannot be borrowed).

- Must not have repaid a TSP loan of the same type in full within the past 60 days. (If you have both a civilian TSP account and a uniformed services TSP account, the 60-day waiting period applies separately to each account.)

- Must not have had a taxable distribution of a loan within the past 12 months unless it was the result of your separation from Federal service.

- Must not have a court order against your TSP account.

For residential loans, the following additional requirements must be met:

A residential loan can only be used for purchasing or constructing a primary residence, which may be any of the following:

- House

- Townhouse

- Condominium

- Shares in a cooperative housing corporation

- Boat

- Mobile home

- Recreational vehicle

A residential loan cannot be used for:

- Refinancing or prepaying an existing mortgage

- Construction of an addition to an existing residence

- Renovations to an existing residence

- Buying out another person’s share in the borrower’s current residence

- The purchase of land only

The borrower’s primary residence must be purchased in whole or in part by you, or your spouse, if you are married.

Why would someone take a TSP loan?

There are probably a lot of reasons someone would take a TSP loan. However, we’ll focus on the two reasons that are probably most common:

- The borrower needs the money.

- The borrower thinks there’s a better use for the money than to leave it in TSP investments.

Let’s look at each of those a little more closely.

TSP Loan Reason #1: The borrower needs the money.

This could very well be a legitimate reason. This is particularly true if there are pressing needs and no other possible source of funds. However, even the TSP loan document warns the borrower about the impact that a TSP loan has on retirement savings. Why? There are probably a couple of reasons. Let’s focus on two:

- The borrower has no other reasonable way to borrow money.

- The borrower believes that a TSP loan is better than their other alternatives (home equity line of credit, refinance, etc.).

For the purposes of this article, we’ll imagine a situation in which there is a perfectly acceptable reason to borrow money. For example, a ‘triple whammy,’ like losing your spouse while transitioning from the military & having to pay for medical costs & respite care…that might be considered perfectly acceptable. Of course, each reader should have their idea about what is considered ‘perfectly reasonable.’

However, our concern is whether a TSP loan is the correct source of capital, not whether the borrower should be taking out a loan.

Under Scenario 1, if there are no other reasonable ways to borrow money (outside of consumer debt, credit cards, TSP hardship withdrawal, and other high-interest forms of debt), then the decision is simple: Do I borrow (or not borrow) against my TSP account for this purpose? In the above example, you could reasonably argue that a TSP loan makes sense, particularly if you’ve already gone through your emergency savings to pay for unexpected medical bills.

Under Scenario 2, you might have to compare the TSP loan against another form of debt, such as a home equity line of credit (HELOC) or a home equity loan. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll compare a TSP loan against a home equity loan, which has a fixed rate for the loan’s duration.

In order to determine which is the better interest rate, you would have to compare the home equity loan against the TSP loan. That should be easy, right? Just figure out the G-fund’s interest rate, and that should be what you’re paying in interest. And since you’re paying yourself interest, it’s a wash, right?

Not so fast. Kitces’ article states that the ‘effective rate’ is really the opportunity cost, or the growth rate of the money that you borrow, had it stayed in the original account. In other words, if you’ve borrowed money that would have otherwise been invested in the I-fund, S-fund, or C-fund, then your effective borrowing rate is the difference between the G-fund and that of those funds for the loan’s period.

Example: Let’s think about it. Imagine a very simple TSP scenario. 5 years ago, the Smiths had $100,000 in their TSP account, all of which was in the Lifecycle 2040 fund. They borrow $50,000 for a 5-year loan. As they repay their loan, they are paying themselves interest at the G-fund’s interest rate of 1.75% (the G-fund’s annuity rate as of January 2013). In that case, a $50,000 loan amortized over 5 years at 1.75% yields a total of $2,256 in interest paid. Sounds good, right?

Let’s compare this to what the Smiths could have received had they remained invested in the 2040 fund. As of December 2016, the L2040 fund’s 5-year average was 10.21%. As of this writing, the year-to-date performance was roughly in line with that number, at 9.78%. For simplicity’s sake, we’re going to use an average annual return of 10%. Had that $50,000 stayed in TSP, at a 10% average annual return, it would have grown to $80,525 over that same timeframe.

In order to do that, the Smiths would have had to borrow the money through a home equity loan, right? Bankrate states that in 2012, 6.5% was a reasonable interest rate for a home equity loan. Using that interest rate as an example, a similar loan amortization would have resulted in a $50,000 loan costing $8,698 in interest. To a lender, no less.

However, the Smiths would still have been better off in the second scenario. If they paid a total of $58,698, but their $50,000 grew to $80,525, they still netted $21,827, which is over $19,500 more than if they took the TSP loan. There are also a couple of observations:

- Leaving active duty. A TSP loan, just like any loan against a defined contribution pension program, is only available while you’re still employed. If you separate or retire, you must repay the loan in full. Otherwise the IRS deems the outstanding loan balance as a taxable distribution.

- Tax treatment. TSP loan repayments are made with after-tax dollars. This differs from TSP contributions, which are pre-tax. The reason is simple: a TSP loan is not taxed (unless it becomes a taxable distribution), so the repayment is made with after-tax dollars. Conversely, interest on a home equity loan (up to $100,000 balance) may receive preferred tax treatment, particularly if you itemize your deductions on Schedule A of your tax return.

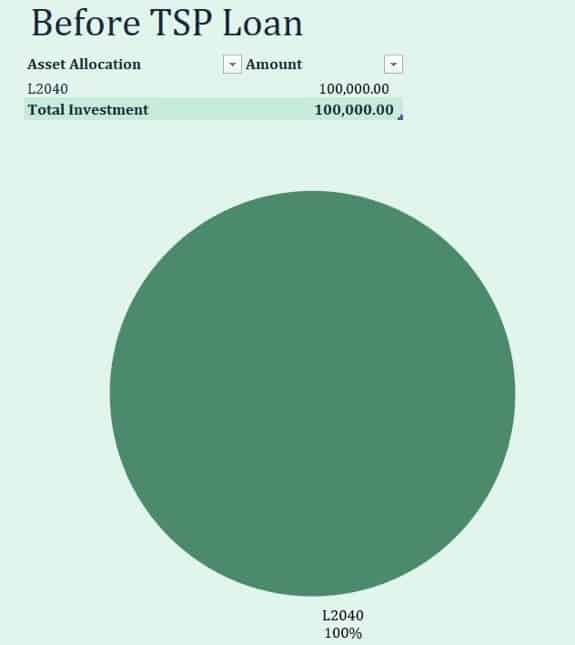

- Portfolio asset allocation. Here is the primary impact to the Smith’s investment. Prior to their loan, the Smiths had 100% of their TSP invested in their L2040 fund.

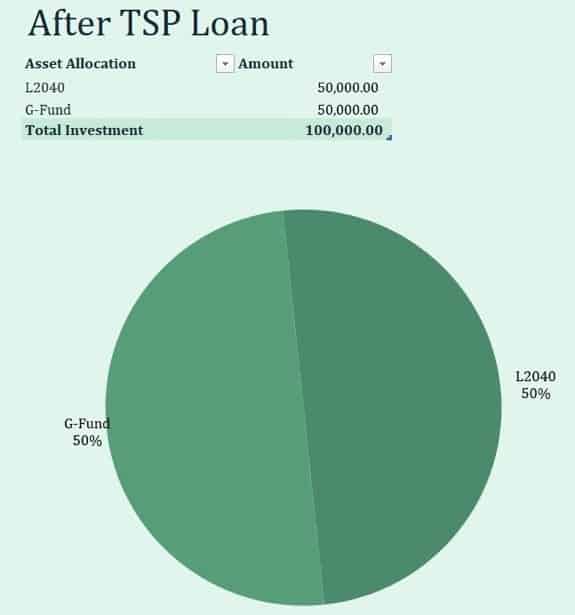

Afterwards, they essentially reduced their L2040 investment by the $50,000 loan, then locked themselves into the G-fund’s rate of return. In other words, their asset allocation looked a lot like this:

Unless the Smiths had intended for their asset allocation to look this way, taking a TSP loan radically changed their investment exposure. The truest danger of a TSP loan is this:

Taking a TSP loan can dramatically alter your investment picture. Unless you account for the impact of locking in G-fund returns on your loan balance, you risk creating a portfolio that is out of sync with your investment approach.

With that said, let’s look into the second reason someone would take a TSP loan.

TSP Loan Reason #2: The borrower believes they have a better use for the money.

For purposes of this article, we’re going to skip a lot of discussion about investment philosophy, risk, etc. We’re going to focus on the use of TSP as a tax-deferred savings vehicle. We’ll compare this to some commonly identified uses of TSP loan proceeds (commonly identified as being what pops up on the first 3 pages of Google Search Results for ‘investing TSP loan’). Here’s what I found:

Using a TSP Loan to Buy a Rental Property (Bigger Pockets.com). Oh boy. We can go down a rabbit hole here. However, let’s say that you’re a first time rental owner. Before we determine whether a TSP loan makes sense, it’s important to actually make sure the purchase makes sense. After all, if you’re not ready to be a landlord, then it doesn’t matter where the money comes from.

Let’s assume you’ve run the numbers & run the scenario by all the real estate landlording mentors that you know. They all agree: this purchase is a good investment. If that’s the case, a bank would probably be willing to finance the purchase. After all, a good deal means that the rental income will be more than enough to make up for all the hiccups that come along the way. And if a bank thinks it’s worth financing, then why would you use your own money to finance the deal in the first place? One of the benefits of real estate investing is the appropriate use of leverage.

If you keep getting turned down by the bank, then maybe the property isn’t a good deal after all. In that case, maybe you shouldn’t a TSP loan on such a risky investment. And if you can get a bank to finance the deal, then you can keep your money growing in your TSP account on a tax-deferred basis.

Can I use TSP to invest in gold or other precious metals? (mentioned on Zacks.com – but it’s such a bad idea we’re not going to link to it)

Sure. You can take the loan and invest in gold, lottery tickets, tulips, or whatever you want. However, when investing in gold, it’s important to remember a couple of things:

- Tax treatment. Gold is taxed as a collectible. Since gold doesn’t pay interest or dividends, the only money you make is when you sell (assuming you sell at a profit). Collectibles are taxed at a maximum tax rate of 28%. This is significantly more than long-term capital gains. Long-term capital gains are subject to a max of 20%. And forget about the tax deferred treatment…that only exists inside the retirement plan. After-tax treatment applies to TSP loan proceeds invested outside the plan.

- Liquidity. You can sell gold relatively quickly. In a worst case scenario, a pawn shop will give you money much faster than you can sell a house. However, the liquidity question is, “How much value does it retain if I have to sell it quickly?” The immediate value of those gold coins that William Devane sold you is the market price of their weight. That’s it. It doesn’t matter if it’s a collectible set of coins with Thomas Jefferson, baby seals, or Thomas Jefferson clubbing baby seals, you’re probably going to get less than you paid for it.

If you weren’t inclined to take a bunch of money and buy gold with it, it’s probably not a good idea to take out a TSP loan.

Taking out a TSP loan to fund Roth IRA (Bogleheads.com)

On the face of it, this seems like a pretty good idea. After all, you’re taking a bunch of tax-deferred money, then using it to fund a Roth IRA, which is tax-free. Here are a couple of considerations:

1. Why wasn’t a Roth part of your investing approach in the first place? After all, TSP accounts don’t grow that large overnight. If you’re making a sudden change just because you want money in your Roth account, you might want to consider why. After all, you’re going to repay that loan with after-tax dollars, so the net result will be fairly similar as if you just started contributing to the Roth IRA in the first place.

However, if you’re in a higher tax bracket, then foregoing the tax deferral on future TSP contributions (because you’re repaying your TSP account with after-tax dollars) doesn’t make sense. You’re essentially giving away your tax benefit by using after-tax money to reimburse yourself. Just use the after-tax contributions to fund your Roth IRA and leave your TSP to grow tax-deferred.

Conversely, if you’re in a lower tax bracket, then you might be better off doing a Roth conversion. If you’ve got a ways to go before separation or retirement, you might consider doing so from a traditional IRA. If you’ve got a lot of cash flow, then max out Roth TSP and a Roth IRA for both you and your spouse.

2. What are you going to invest in with the Roth IRA that you can’t do inside TSP? Before going any further, it’s best to understand what you are going to invest in. If you’re looking to diversify your portfolio, you might want to make sure you understand what you’re going to diversify into. That way, you’re not just paying more money to invest in bunch of index funds that do the same thing that TSP does.

However, this particular thread is interesting because of the ‘unique’ situation this person is in:

Due to some unanticipated expenses it is doubtful that my wife and I will be able to max out both our traditional 401ks and Roth IRAs. I place a higher value on fully funding the Roth since we plan to retire by the age of 50 and know that we can withdrawal our contributions without penalty until we hit 59.5. With that said, I want to continue to max out our 401ks because tax advantaged space should not be left on the table.

My thought is to take out a 1 year $11,000 TSP loan at 2% towards the end of the year to fully fund our Roth IRA while still maxing out our 2015 401k tax advantaged space.

The alternatives are to keep the money in the 401k and forfeit funding the Roth IRA this year or to significantly reduce our current TSP/401k contributions and fail to max out this year. Please explain how either of those options is preferable to my proposal.

In other words, I don’t have enough cash flow to max out my contributions this year. I want to have my cake and eat it too. If that’s the case, then I wonder several things:

- Will these expenses disappear between now and next year? If this couple had been dutifully maxing out both accounts, and there was an emergent one-time expense, this might make sense. However, they would have to have the cash flow to pay off the TSP loan and max out their investments next year.

- Is it possible to fund their Roth IRAs next year? The deadline for Roth IRA contribution is actually the tax return due date. For 2017, the Roth IRA contribution deadline is April 17, 2018 (tax day falls on the next business day after weekends and holidays). If this couple is so cash flow positive, I’d rather see them use the first four months of the next year to fund their current year Roth IRA, then max out the following year’s contribution.

However, you can’t use TSP loan proceeds to exceed the Internal Revenue Code’s IRA contribution limits. Essentially, if you have the cash flow to max out all your contributions, you could take a TSP loan, then repay it back. But you’d have to put the TSP loan proceeds into an after-tax account. In that case, you’d be putting the loan proceeds into a taxable account, at the expense of your tax-deferred savings vehicle. That doesn’t make sense, either.

I might take a $30,000 401k loan just to piss some of you off (PunchDebtintheFace.com). This is pretty funny, and actually appeared higher on Google rankings than the previous two. I kept it for last simply for the humor value.

While I might not agree with the fundamentals in this article, this person seems to have enough money set aside to afford repaying the loan. His true question seems to be, “What is wrong with taking a 401(k) loan (or TSP loan, which he actually references in the article), then paying yourself the interest?

I’d say nothing is wrong, if that’s your fundamental approach. But then, why would you go through the trouble of doing that when the net effect is the same as taking $30,000 in your TSP and putting it into the G-fund? Either:

- You weren’t going to invest that much money in the G-fund as part of your allocation strategy. In that case, borrowing it just to pay yourself back at the G-fund rate doesn’t make sense.

- You were going to invest that much money in the G-fund as part of your strategy. In this scenario, it would be simpler to just keep the money in your TSP and invest that much in the G-fund.

Conclusion

It appears that TSP loans do have a place. If you need a loan, but don’t have any options, then a TSP loan makes sense.

However, the dangers of borrowing money to earn a better investment still exist. They’re actually even more substantial than if you used a more traditional means, such as a HELOC. First, you run the risk of losing money on your investment. Second, you run the risk of underperforming what you would have earned had you left the money alone. Third, you’re jeopardizing your retirement plan on this outcome. Finally, if you aren’t able to repay yourself, the loan can become a taxable distribution. A taxable distribution is subject to full taxation and any early withdrawal penalties that may apply. Ironic, huh?

If you don’t pay yourself back, you don’t owe yourself… you owe the IRS.

So what do you think? Feel free to post your comments below.

Comments:

About the comments on this site:

These responses are not provided or commissioned by the bank advertiser. Responses have not been reviewed, approved or otherwise endorsed by the bank advertiser. It is not the bank advertiser’s responsibility to ensure all posts and/or questions are answered.

CathiB says

I took a 5 year TSP loan ($10,000) a few months ago. In hindsight, probably wasn’t the best idea. Now, I have an extra $500/month I could throw at it or I could find somewhere else to invest. Suggestions?

Ryan Guina says

Cathi, I’m a big fan of paying off debt. There is generally little downside to paying off your debt and a lot of positives, such as increased monthly cash flow and not having to worry about what happens if you are unable to repay the loan (this article covers the downsides more thoroughly).

CathiB says

Thank you Ryan. Just made a dent towards getting it paid off.

Buzz says

I think I’ll take a 50k TSP loan for a VRBO rental just to **** people off.

PETER CONNOLLY says

When TSP loans are paid back, they are paid back with AFTER TAX dollars. When you do retire and take that same money out from your traditional TSP you will be TAXED again. Double taxation on your loan is NEVER good.

BZ says

Yes and no. The principal portion of your loan is your pre-tax money. It doesn’t matter if you’re paying it back with after-tax money (you’re paying yourself back), it’s only taxed once (when you take it out).

However, the interest portion of your loan is not really “interest”, it’s your own, hard-earned, after-tax money. When it’s taken out at retirement it is definitely taxed again.

Dan says

Only the interest is double taxed. I’m not saying that’s nothing, but you’re completely wrong that it all is double taxed. With rates as low as they are (and are likely to remain) it’s the least relevant part of the discussion. Interestingly enough, someone who took a loan out at the beginning of this year would be sitting much better for having done so. There are too many variables to say whether or not it’s a good idea to take one out. The only variable that I DO think deserves mention above all others is the possibility of losing your job during repayment and having to pay a penalty for the distribution. That is a huge concern, and honestly my biggest issue with these loans. I think that the option should exist to continue making payments on your own in that case. It would be a travesty to be unable to leave your job for a very good reason but be stuck for a loan.